How Data Centres Work | Part 2

Data centre operators are extremely risk averse. From the point of view of your average commercial property occupier the levels of risk aversion can seem unnecessary or even paranoid. After all, you can insure your way out of most risks. It is perhaps only when you consider the nature of the operation that it becomes more apparent why data centre operators treat risk as something to be avoided at all costs. Ensuring that data centre site selection risks are managed propertly is therefore fundamental to a successful project.

The ‘How Data Centres Work’ series

1. Introduction

2. Risk

3. Power

4. Connectivity

Colocation and risk management

For data centres offering colocation (where space is rented out to tenants) risk management is critical. Firstly, reputational damage associated with any loss of service to their customers is catastrophic. Like a hospital being found to contain superbugs, very few people will want go there regardless of anything else.

Secondly, in addition to signing a lease, data centre operators must also agree a Service Level Agreement (SLA). SLAs put a set of performance standards on the data centre operator that, if breached, result in punitive liquidated damages being awarded to their customers. A one-second power outage could trigger a one month rent credit. Additional awards may continue to be granted for every further second of an outage. Operators will offer guarantees for many other breaches. Doors being found unlocked. Humidity or temperature within the data halls falling outside set parameters. Even the rate of change in temperature exceeding agreed limits.

Financial risk

An outage of just a few minutes could be financially devastating for a data centre operator, and often either a sustained breach or a series of consecutive breaches can result in the customer being able to terminate their rental agreement with the data centre operator. Since most data centres have build costs reaching into the tens or even hundreds of millions of dollars, the risk of rental income being threatened is out of the question.

Internal vs. External Risks

You can manage many risks by good design and by putting in place systems and practice that reduce or eliminate single points of failure. For example, if the power fails, there will be a backup generator. If there is a surge or dip in the power supply, an Uninterruptible Power Supply (UPS) unit will smooth out the power. And if one of those pieces of equipment fails, there will be a spare. The level of redundancy in a data centre is described by N being the amount of equipment required for normal operations; N+1 meaning there is one spare piece of equipment on standby; and 2N meaning there is double the amount of equipment required for normal operations.

For example, a data centre which requires 3MW of clean power might need 3 x 1MW units of UPS for N redundancy; 4 x 1MW units for N+1; 5 x 1MW units for N+2 and 6 x 1MW units for 2N . For many years the Uptime Institute has offered third party inspection and certification of the design, construction and operation of data centres to describe these levels of resilience.

Avoid over-engineered designs

The customer and the use will determine the proper level of resilience. Since rents are relatively commoditized, customers are unlikely to pay a higher rent for features which they deem to be surplus to requirements. Some occupiers such as financial trading companies are willing to pay a high rent for an equally resilient facility since the cost of an outage when there is a multi-billion-dollar trading position open would be unthinkable. For others, such as content delivery network (CDN) providers, an acceptable level of risk is good trade-off for a lower rent.

Stop, Security!

Data centres incorporate physcial measures alongside security protocols to minimise the risk of trespassers disrupting their operations. From the outside security measures might include high fencing and constant CCTV surveillance, external guard houses, powered gates with vehicle traps and anti-ramming barriers. In the 2000s when enterprise banking data centres were designed and built on a ‘money-no-object’ basis we saw external security features such as active radar tracking of every individual, blast-proof walls and multi-layered fencing with infra-red sensors.

Internal security starts at reception where users must normally be pre-booked or pre-vetted in order to gain access beyond the lobby. Man-traps are frequently used to avoid tail-gating. Often the man-traps will include scales to weigh visitors and ensure nothing is being sneaked on or off site. Biometric security such as fingerprint, blood vessel or iris scans are common. There will also be layers of security so that even if a miscreant makes it through the lobby they cannot access the data halls.

Data centre operators will determine the level of security based on the needs of their customers. All security measures add cost to the building and operating expenses for a data centre, and with colocation rents being highly competitive there is little room for unnecessary costs.

External Risks

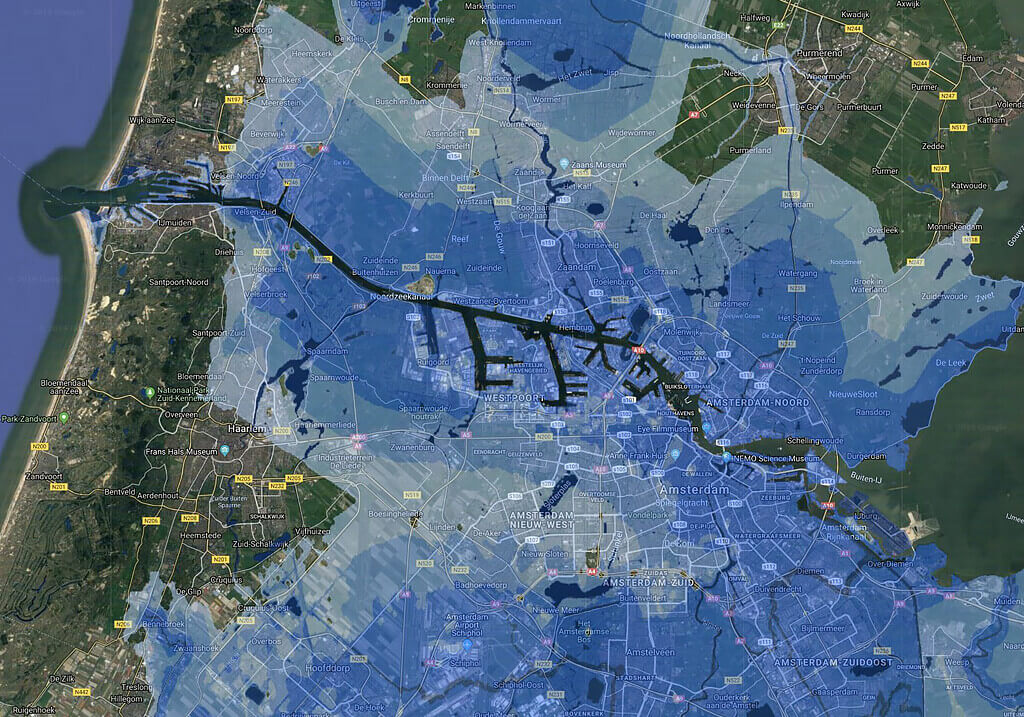

In the words of the great Kirstie Allsopp, it’s all about Location, Location, Location. Risks are effectively managed by avoiding building in the wrong place. Among natural hazards, the risk I hear most concern for is flooding. But it is by no means the only natural hazard. Other risks include earthquakes, ground instability, wildfire and wind. Then there are the man-made hazards. These include being located under a commercial flight path or being located close to hazardous facilities such as a chemical plant.

What lies beneath

Data centre site selection risks extend to the the land itself. Building on brownfield sites helps regenerate areas. Access to existing services infrastructure is simpler, but brownfield land can be problematic. Contaminated land is a major issue, especially where the party responsible for the pollution no longer exists. The risks continue underground; whether unexploded ordinance from World War II, or unknown gas or steam pipes. Searching only for greenfield options is not without risk, especially if a site has not yet obtained planning permission. In many cases, development can be halted entirely by the discovery of protected wildlife such as bat or newt colonies.

There are also soft risks that need to be managed. It is generally a bad idea to locate a data centre too close to residential areas on account of the noise pollution from whirring chillers and backup generators starting up in the dead of night. Then there is the risk of government policy change, such as Amsterdam’s recent moratorium on any new data centre development. In certain areas high levels of criminal activity may present a major risk to the operation of a data centre or to the people travelling to and from work. There is the issue of access. If a site is too remote or if public transport links are poor, recruiting site management may be a problem.

Risks, in conclusion

You should always make efforts to avoid risk. However, sometimes data centre site selection risks are unavoidable. If you want to build in the Netherlands, for example, you are almost certainly going to be building in a flood zone. While every data centre operator will tell you to avoid building under a flight path; yet the largest data centre cluster in the world, in Ashburn VA, happens to be directly on the approach path for Dulles International Airport.

Sometimes that’s the price you pay for being in a market. Your site faces the same risk experienced by every data centre operator in the area. Some customers and cultures will be less concerned by risks, while others will be preoccupied by them. The key to managing risk is to understand your market and to understand and respond appropriately to the concerns of your prospective customers.

Next in the Series – Data Centre Power. We look at how much power a data centre needs and how data centre operators try to increase efficiency.

Image: Vertiv

Flood Map of Amsterdam (SwissRE CatNet)

Unexploded WWII bombs present a potential challenge for

European developers (Image – Holger Weinandt, copyright CC by SA)