How Data Centres Work | Part 1

I have often been asked to explain to property professionals what data centre operators look for in a development site. Talking the matter through with them further, I realise that there is a great deal of confustion about just what a data centre is, and how data centres work. Thus was born a blog.

Usual disclaimer before we proceed, this series of articles is for information purposes only and does not constitute formal professional or legal advice.

The ‘How Data Centres Work’ series

1. Introduction

2. Risk

3. Power

4. Connectivity

When is a data centre… a data centre?

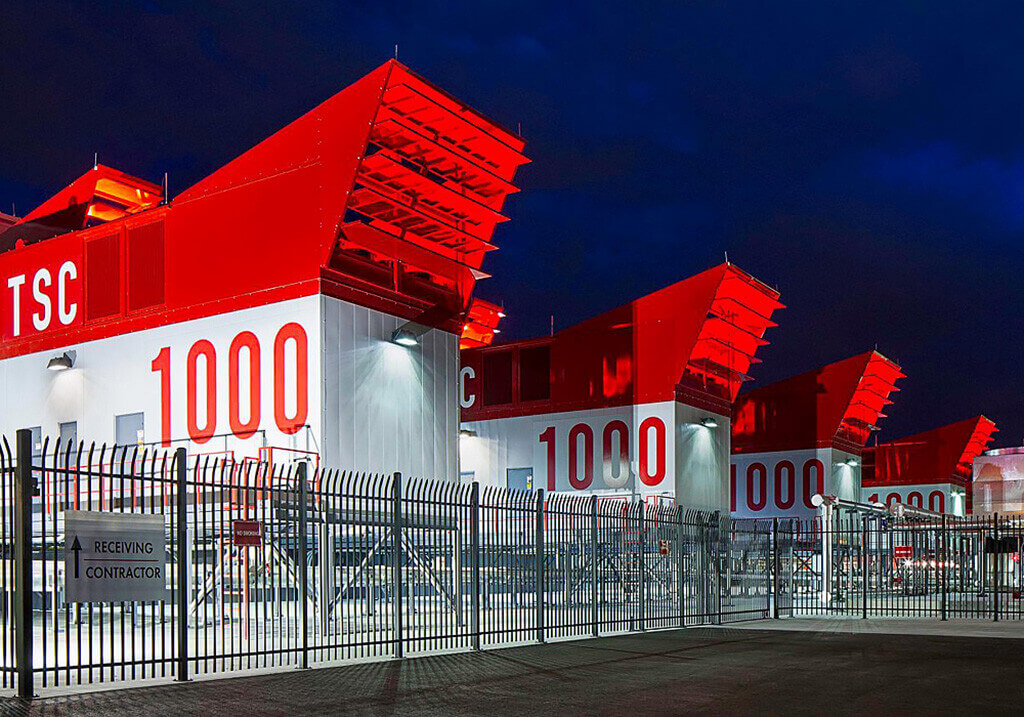

If you work in a reasonably-sized office you may have seen a windowed door with a little window, with little LEDs blinking in the darkness and the loud whirr of an air conditioning unit. In this small space, whether it’s a Secondary Equipment Room (SER, also known as a comms room) or a Main Equipment Room (MER), here you have all the makings of a data centre – security, cooling, power, computing and connectivity. So where do we draw the line between an office computer room and a data centre? For me, a data centre is a data centre when the overwhelming purpose of the facility is for the receiving, storage, processing and distribution of electronic data. So a facility can have many data centre-esque attributes without being a data centre.

What makes a data centre?

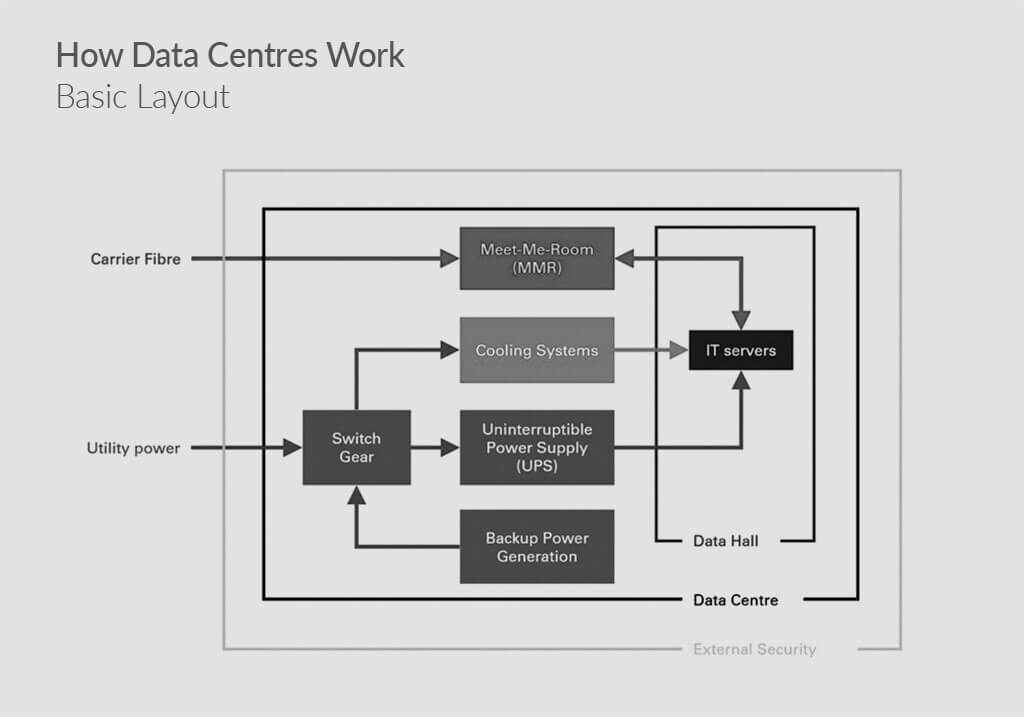

If we take the principles that apply to your office IT room and scale them up on a dedicated site, you have the basics of how data centres work. Power is delivered from the local utility company and arrives at the Switch Gear, which sends some power to cooling equipment (which regulates the temperature of the data halls), some to other building services, and the rest to the Uninterruptible Power Supply (UPS) unit. The UPS unit combines a short amount of battery power – say 15 minutes – for the servers as well as acting to ‘clean’ the incoming power by removing any surges or dips in the grid. Finally, power is delivered to the servers in the Data Halls.

For connectivity, carrier fibre arrives into the data centre and terminates in the carrier’s server in a Meet-Me-Room (MMR). The servers will then need to be connected from the Data Halls to the MMR by a separate internal connection.

One of the tenets of data centre operation is to keep the servers live at all times. For this reason most data centres incorporate elements of physical security including high walls, CCTV, manned security, motion tracking, biometric scans, and man-trap doors. They will also have strict access requirements with visitors needing to be pre-booked and vetted prior to appearing on site. The level of security will depend on the activity and the nature of the customers of the data centre. You can imagine banking data centres are highly secure, whereas data centres hosting Netflix content servers will be less so.

As well as physical security, data centre operators need to factor in the likelihood of equipment failure, and so multiple levels or resilience are often baked into their design. This is normally grouped into Mechanical Resilience comprising Heating Ventilation and Air Conditioning (HVAC) and Electrical Resilience which is mainly determined by the resilience within the UPS systems. Understanding these core elements is key to understanding how data centres work.

More security and resilience means more operating expenses which ultimately means higher rents, so the market tends to arbitrate the appropriate level of security for the use.

A brief history of data centres

While you could debate their origins, based on my definition the first dedicated data centres for commercial purposes emerged either in the 1970s. In the late 70s Systems Integrators (SIs), such as Sungard at their 401 Broad Street Philadelphia facilty, began building IT facilities off-premises to their clients to manage their data. Otherwise in the early seventies when Telecoms Companies (TelCos) began to manage commercial and government data storage.

Around the same time banks and financial institutions began to move their IT servers into dedicated facilities which they built, owned and operated. Facilities that are owned and operated by their end users are known as Enterprise facilities, and we collectively refer to this group – SIs, Telcos and financial institutions – as having Legacy Enterprise data centres.

Cometh the hour, cometh colocation

It was not until the early 1990s when the concept of renting server room space from a third party, known as ‘colocation’ (and abbreviated to colo) became a reality. You can imagine the nervousness of company IT directors giving their most precious assets to a stranger. Yet in time, colo operators earned the trust of the IT industry and proved themselves to be reliable stewards of their custmers’ servers. Since the majority of demand for IT space in the 1990s and 2000s was from the financial sector, data centre operators in Europe predominantly based themselves around financial centres – Frankfurt, London, Amsterdam and Paris, which later became known as the FLAP markets – and to this day they remain some of the largest data centre markets in the world.

The Enterprise Strikes Back

In the past decade, two groups have come to dominate demand for new data centre space; public cloud and social media. Demand has been so high, in fact, that in many cases it has outstripped the considerable supply provided by colocation. In addition, several of these companies prefer to deploy massive sites, on a scale that is far bigger than a colocation data centre is built to handle. As a result we have seen a return- in part- to Enterprise data centres making a comeback by the ‘Hyperscale’ companies. We describe these facilities as Hyperscale Enterprise, as opposed to the Legacy Enterprise facilities of old. Colocation has been catching on, however, and many data centre operators are working with Hyperscale companies on a build-to-suit basis. Several others have attempted to capture Hyperscale Enterprise demand by securing large amounts of powered land in the hope of agreeing ground rent or powered shell type deals. Notable examples include Equinix’s new xScale initiative and Digital Realty’s Powered Base Buildings.

Next in the Series – Managing Risk in Data Centres. We look at internal and external risks and how risks are viewed and managed.

Most data centres follow this basic power, cooling and connectivity layout