How Data Centres Work | Part 3

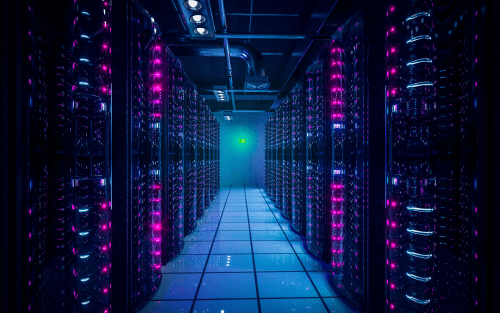

Data centres use a lot of power. So much so that, unlike all other asset classes within real estate, data center operators charge rent not by the square metre or square foot, but by the kilowatt (kW). In this section we look at some of the considerations data centre developers have to make in order to maximise energy efficiency and optimise data centre power appeal.

The ‘How Data Centres Work’ series

1. Introduction

2. Risk

3. Power

4. Connectivity

Unlimited power!

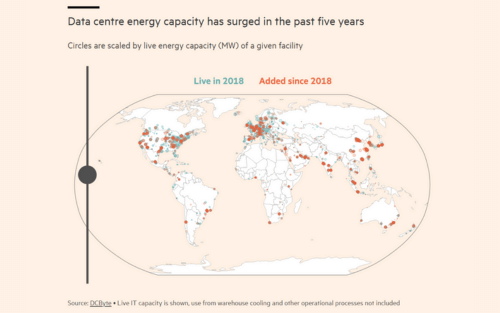

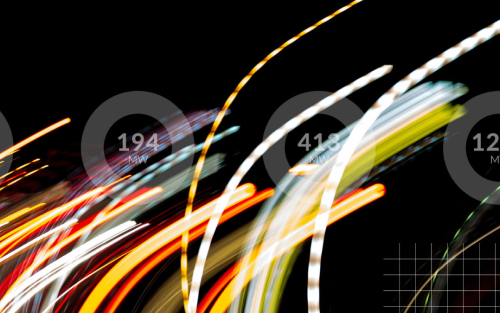

But just how much is a lot? For a small data centre the power demand might be 2 megawatts (MW). For comparison, when you boil a kettle it uses about 2kW power. So the eneregy required for a small data centre is about the same as 1,000 kettles, or about 300 homes.

At the other end of the scale, the biggest data centres draw well in excess of 100MW of power from the grid. We will need a bigger point of reference than kettles, so let’s go with the nuclear reactor of a Nimitz-class aircraft carrier, which generates around around the same amount of electric power and could provide energy for around 16,000 homes.

Danger, Danger – High Voltage!

Electricity consumption forms one of the biggest ongoing expenses for a data centre operator. One way to reduce the power bill from the outset is to reduce the energy losses within the transmission system. Once electricity has been generated it must be transported to the end user. The higher the Voltage, the lesser the energy that is lost during transit. Whenever the Voltage is stepped up or down at a transformer a small amount of energy is lost as sound and heat. A good data centre location is therefore one that is not too far from a high voltage grid connection, and preferable where there is a minimum of distance. It is not surprising therefore to see substantial super-high voltage substations next to many of the new Hyperscale data centre developments.

Green matters

Despite what a recent bbc documentary might suggest, the sector is acutely aware of their electricity consumption and of the need for reneweable energy. Both Google and Microsoft already use 100% renewable power, and Amazon is currently over 50% and with commitment to 100%. For anyone looking to sell data centre development sites to a hyperscale user, access to renewable sources is now mandatory.

The challenge with sourcing renewable power is that it is not the only factor when considering where to locate a data centre. The Nordic region, for example, has abundant cheap renewable power from hydro-electic generation, but if you need your servers to be in Germany for data sovereignty reasons then you must search for renewable power in Germany, where much of its energy is still generated by burning fossil fuels.

Power Usage Efficiency

With data centres consuming so much energy, there is a keen focus on improving their efficiency. We use Power Usage Efficiency (PUE) as a measure of total energy consumed versus amount consumed by the servers. In the last twenty years, PUE has improved dramatically. Back in 2000 we considered a PUE of 1.8 to be excellent; now a good PUE is below 1.1. There are certain environmental factors that can help achieve a lower PUE. This could be a colder climate, or access to sources of cool water.

One problem we are finding in certain markets is that PUE can mask consumption of scarce resources, especially water. In certain data centres in the US, for example, mains supply water is used in open loop cooling systems to minimise power costs, but in regions where water scarcity is a live issue it is difficult to describe such data centres as truly sustainable, even if they are efficient from a PUE perspective.

Power Pinches

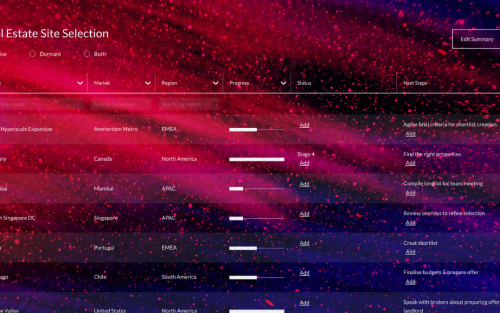

Data centres like to cluster together. There are a few reasons for this, but mostly it boils down to being able to physcially network with one another and/or absorb the overflow of customer demand from one data centre to another. The problem with this behaviour is the strain that it causes on the local power grid infrastructure, most of which was never designed to take on such high capacity requirements. In certain markets such as Frankfurt or London, sites with power have become rarer than hens’ teeth, and operators will fight with one another to secure powered land in the lead markets. The result is either a wait of years for additional power capacity to come online, or paying substantially over the odds for powered land.

Some operators are taking the opposite approach and looking for power hotspots and developing their data centre plans around what would normally be the limiting factor. CloudHQ, for example, has taken to developing a new data centre campus in the shadow of the old Didcot B power station.

Another approach for data centre operators is to side-step the grid altogether and to generate power themselves. Not only does this eliminate transmission consts which may account for around 1/3 of a typical electricity bill, but it also can substantially reduce connection times. Although data centres do have onsite backup generators, these are normally not suitable for prolonged use. Backup power is typically provided by diesel generators which are fairly high emitters of particulate carbon and greenhouse gasses. What’s more, backup power is supposed to always be a secondary source of power as the name implies. So a separate system is necessary. In Ireland, US operator Edgeconnex used gas turbines to power its data centre when the grid was not able to supply its data centres. Other data centres, such as Swedish newcomer EcoDataCenter, uses an onsite Combined Heat and Power (CHP) system to both power its servers and provide heat for nearby industrial processes.

Growing pains

The issue of balancing demand for ever-increasing amounts of power with sustainable sourcing is possibly the biggest challenge facing the industry. With data centres estimated to be one of the largest users of power in the coming decades, it is crucial for operators to think carefully about their long term power strategy and not simply to rush from one project to another. I am confident however that the sector will rise to the challenge.

Next in the Series – Data Centre Connectivity. We look at the language used by the sector, key technologies and considerations for the future.